1

Leverage existing integrated care models

delivery of coordinated care, reduction of waste and burden on the system and protect risk groups.

A chain is only as resilient as its weakest link. Different actors and organizations operative within the healthcare value chain or -system, possess different capabilities to absorb shocks. Yet, the system relies on them staying functional. COVID-19 puts acute strain on hospitals and their affiliated organizations.

“We are in this together. And we will get through this together”

Those are the words of António Guterres, Secretary General of the United Nations, talking about the COVID-19 pandemic. These words and subsequent actions have become apparent on hospital floors in the everyday struggle to cope with COVID-19. Healthcare is a complex system, and during the exceptional situations caused by COVID-19, it has shown the importance of the interrelatedness of different components of the healthcare system for outcomes such as patient safety and quality.

Different entities within the system bring different capabilities to the table to absorb the shock by such an acute crisis of this magnitude. For example, the emergency surge capacity of the majority of hospitals around the world has been exceeded through the inflow of patients with COVID-19. In addition, employees have to cope with the uncertainty regarding following the constant development of relevant treatments and recommendations. On the front lines, there have been a lack of beds and staff, as well as a shortage of personal protective equipment and other critical material such as ventilators. Apart from shortages in resources, spatial confinements also arose quickly. Many hospitals experienced a lack of isolation capacity, which caused difficulties in terms of separating infected patients from those not infected with the virus [1]. Individual departments and clinics were unable to meet these challenges alone. Hence, to understand and learn from this experience, it is important to apply a systems perspective, which will be done in this chapter.

To handle the COVID-19 related demands put on the health system, various strategies were applied by different countries. A large Australian study investigated whether there is a relationship between (a) a government’s capacity to respond, (b) the response stringency and (c) the scope of COVID-19 testing with cumulative and daily new COVID-19 cases and deaths in March and April 2020[2].Response stringency captures the extent of strategies such as closing schools and workplaces, cancelling public events, closing public transportation, introducing gathering restrictions, restricting internal movements or implementing international travel controls[3].

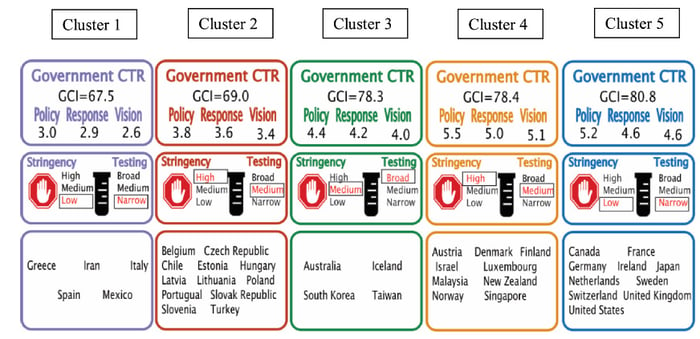

To get a general overview, the 40 studied countries were categorized according to these characteristics (a–c). This resulted in five clusters where countries that are similar on their global competitiveness index (GCI)[4](i.e., productivity, growth and human development) as well as stringency and testing, are grouped together (see Figure 1).

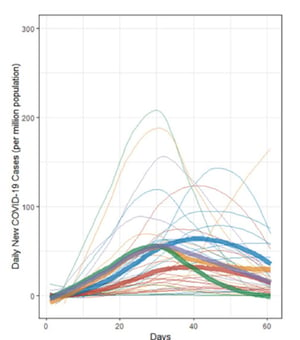

In the next step, Braithwaite and his colleagues showed that early stringency in measures taken and broad testing were crucial in the response to COVID-19. For example, those countries that adopted stringency measures relatively early paired with a broad testing approach (Cluster 3 in green), were those that most successfully flattened the curve of new COVID-19 cases (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Original figure from Braithwaite et al [2]. Graphical summary of national health system capacity to respond and adopt early stringency measures and approaches to COVID-19 testing.

Figure 2. Original figure from Braithwaite et al [2]. Spaghetti plots of daily new COVID-19 cases in 40 national health systems over the 61 days examined (1 March to 30 April 2020). Individual national responses are represented by thin lines. Thick lines are the mean changes for each cluster over time. Lines are smoothed using locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) regression.

However, through COVID-19, it has also become apparent that healthcare systems in many countries, in general, proved unprepared to meet the high level of stress that accompanied the pandemic. Consequently, the majority of available resources within the system were allocated to the clinical treatment of COVID-19, putting regular health and social services on hold. This, in turn, has contributed to the build-up of unmet demand and increased frailty of the system[5]; demands, that the healthcare system will need to handle or deal with in the future.

In healthcare, several types of systems can be differentiated. Whereas healthcare systems represent the general organisation of how healthcare services are coordinated and delivered on the national level, the hospital system encompasses factors on the organisational level, that involve different functions (e.g., communication, leadership) as well as departments and clinics. In this chapter, we will next address the resilience of the hospital system and present three potential coping strategies (COVID-19 command centres, integrated care and the reallocation of roles and responsibilities) that were used to maintain the functioning of hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

System resilience implies being prepared for and effectively responding to crises through the reorganisation of systems to manage the new conditions while maintaining core functions[6]. This definition can be applied to different levels of health systems (e.g., national level or organisational level). Standardised procedures are necessary for effective functioning and security and to be able to reach quick decisions. However, even during non-COVID-19 times, the coordination of information, problem-solving processes and decision-making amongst the different actors and organisations within the healthcare system is often haphazard and not based on accurate or real-time data. During COVID-19, these difficulties are accentuated and the relevance of information and a valid basis for decision-making increases[7].

To maintain or rebuild resilience within a complex system, four dimensions are essential [8]. In the absence of these preconditions, it will be difficult to make decisions.

We would like to exclude the question of actor legitimacy in this chapter and focus on three strategies that seem promising based on the cases we reviewed. These effective strategies bolster interdependence, knowledge generation and anticipation through integrating information flows, creating transparency and ensuring adequate capacity management to prevent the collapse of the hospital system. First, an integrated care model is presented as a cross-disciplinary solution to organise and align different actors and organisations within the healthcare system. This is followed by the reallocation of roles and responsibilities based on a standardised approach to care. Last, specialized COVID-19 command centres are presented as a strategy to facilitate working with COVID-19.

delivery of coordinated care, reduction of waste and burden on the system and protect risk groups.

Standardization of information protocols in order to increase broad knowledge about the current situation within the organization.

It’s the same concept of mission control at NASA or air traffic control but applied to hospitals.

To maintain or rebuild resilience within a complex system, four dimensions are essential.[5] In absence of these preconditions it will be difficult to take decisions.

We would like to exclude the question of actor legitimacy in this article and focus on three learnings we’ve drawn from the case studies we reviewed. They display effective strategies to bolster interdependence, knowledge generation and anticipation.

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, it became evident that healthcare systems are still not integrated enough [5]. In general, the lack of integration has also been identified by scientific studies [9] as an obstacle to the delivery of coordinated care, reduction of waste and burden on the system. COVID-19 has, in particular, posed a danger for older and vulnerable people as well as people with pre-existing conditions. Integrated care, that is, the integration of health and social care, has been found useful to protect these risk groups as well as provide the necessary care during the pandemic.

Norrtälje municipality has so far handled the challenges of COVID-19 better than the other municipalities in the Stockholm region.

Another interesting approach was presented by two healthcare systems using the standardization of information protocols to increase broad knowledge about the current situation within the organisation. The benefits of standardised care protocols for the treatment of COVID-19 have been demonstrated (e.g.,[10]): patient populations show less variability and an improvement in clinical outcomes.

care model based on a standard calendar, organisation-wide hygiene standards, rounding following identify, situation, background, assessment and recommendation (ISBAR)

A command centre is a physical space that enables team executives and leaders to continuously collect, analyse and disseminate critical information on key issues and translate these into strategies and goals for crisis management [11]. “It’s the same concept of mission control at NASA or air traffic control but applied to hospitals” [12]. Through the systematic collection of vital information in one place, command centres enable fast response to new developments and rapidly spread awareness[5]. Command centres in hospitals, in general, have become more popular to secure communication and coordination amongst the complex hospital system and ensure efficiency and high quality care. Ultimately, the function of command centres is to foresee challenges and adapt to them by installing relevant strategies to manage and provide a work environment that allows employees to provide their best performance.

“Mission control” COVID-19 is about attaining the greatest possible control over the situation and moving from a reactive approach to a proactive one.

Through the Command Center the hospital gathers 24/7 real-time data via 60 Apps or so-called “Tiles”.

Rega was mandated to monitor and analyse the national ICU patient data and to act as an intermediator for patient transfers between the 76 ICUs in the country.

In this chapter, we have established the need for a stringent response to a pandemic like the one starting in 2020. Stringency relies to a large extent on a system’s ability to align the actions of different actors, to share and combine knowledge, and to support them in anticipating unknown situations.

Through integrated models of collaboration and standardised processes of the system on the micro and macro level, we believe that stringency of response can be augmented. It will also facilitate the exchange of real-time data or even predictive abilities of the information model.

To conclude, collaboration across different entities within the hospital system as well as across different institutes within the healthcare ecosystem seems crucial in times of the massive challenges that acute care hospitals face due to COVID-19. By finding ways of working together, not only is information flow increased, but also transparency and overall capacity.

[1] Klein MG, Cheng CJ, Lii E, Mao K, Mesbahi H, Zhu T, et al. COVID-19 Models for Hospital Surge Capacity Planning: A Systematic Review. Disaster Med Public Health Prep [Internet]. 2020/09/10. 2020;1–8. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/covid19-models-for-hospital-surge-capacity-planning-a-systematic-review/64C79F32198135FBEC263535F4108F65

[2] Braithwaite J, Tran Y, Ellis LA, Westbrook J. The 40 health systems, COVID-19 (40HS, C-19) study. Int J Qual Heal Care [Internet]. 2020 Sep 30; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzaa113

[3] Coronavirus government response tracker [Internet]. [cited 2021 Feb 8]. Available from: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker

[4] Schwab K. The Global Competitiveness Report 2019. 2019.

[5] Stein KV, Goodwin N, Miller R. From Crisis to Coordination: Challenges and Opportunities for Integrated Care posed by the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Integr Care [Internet]. 2020 Aug 12;20(3):7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32863805

[6] Chua AQ, Tan MMJ, Verma M, Han EKL, Hsu LY, Cook AR, et al. Health system resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from Singapore. BMJ Glob Heal [Internet]. 2020 Sep 1;5(9):e003317. Available from: http://gh.bmj.com/content/5/9/e003317.abstract

[7] Vetterli C, Roth R. WHITEPAPER Lean Operations Center : Sicherheit für Planung und Steuerung in COVID-19-Zeiten. 2020.

[8] Blanchet K, Nam SL, Ramalingam B, Pozo-Martin F. Governance and Capacity to Manage Resilience of Health Systems: Towards a New Conceptual Framework. Int J Heal Policy Manag [Internet]. 2017;6(8):431–5. Available from: https://www.ijhpm.com/article_3341.html

[9] Braithwaite J, Mannion R, Matsuyama Y, Shekelle PG, Whittaker S, Al-Adawi S, et al. The future of health systems to 2030: a roadmap for global progress and sustainability. Int J Qual Heal care J Int Soc Qual Heal Care. 2018 Dec;30(10):823–31.

[10] Zhang P, Duggal A, Sacha GL, Keller J, Griffiths L, Khouli H. System-Wide Strategies Were Associated With Improved Outcome in Critically Ill Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019: Experience From a Large Health-Care Network. Chest [Internet]. 2021 Feb 8; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.029

[11] Ruggeri C, Chiu E, Niemeijer T, Johnson T, Worsfold A. COVID-19: The Hub of Recovery and Resilience, Command Center. 2020.

[12] Noon C. The English patients: This UK hospital is harnessing AI to make decisions. [Internet]. GE healthcare. [cited 2021 Feb 2]. Available from: https://www.ge.com/news/reports/the-english-patients-this-uk-hospital-is-harnessing-ai-to-deliver-slicker-service